Reading Length: 10 Minutes

Key words: Political Theory, History, China, Founding Fathers

John Adams was an American statesman who served as the first Vice President under Washington and the second President. A lawyer, Adams served as a diplomat during the Revolutionary War. He was an activist for the then-novel concepts of the right to counsel and the presumption of innocence. Although a staunch patriot, he defended the British soldiers in court involved in the Boston Massacre. Adams was one of the only early American Presidents that was not a slaveowner.

Less well-known is the political philosophy of Adams. After retiring from political life, Adams tended his farm through old-age and rekindled his friendship with Jefferson, sending a series of letters that included philosophical reflections on their respective political theories.

When Adams’ political philosophy is brought up, he is derided as a monarchist or royalist. It is often believed that Adams wanted to establish an American nobility through titles and other gestures. On deeper inspection, however, the political philosophy of John Adams is a nuanced and prescient perception of the problems that would arise in American political life.1

Natural and Unnatural Aristocracy

Contrary to popular wisdom, Adams did not advocate for a nobility in America. In a letter to Jefferson, he insists:

I will forfeit my life if you can find one sentiment…which, by fair construction, can favor the introduction of hereditary monarchy or aristocracy into America.2

Aristocracy, in its original greek aristoi, literally means rule by the best. It is hard to see why this would be a bad thing, compared to rule by the worst, and the term generally had positive connotations for ancient Greeks.

By the time of the Enlightenment, however, the term aristocracy had become closely associated with a corrupt and incompetent nobility. Thomas Paine, in his Rights of Man, puns:

This is the general character of aristocracy, or what are called Nobles or Nobility, or rather No-Ability, in all countries.

The new Americans found themselves in power with barely any vestige of a noble class, so they sought to reclaim the concept of aristoi.

Jefferson created a contrast between the aristoi and the pseudo-aristoi. The natural aristocracy were those naturally endowed with exceptional intelligence and ability, while the pseudo-aristocracy were those who only got their power and station in like through hereditary means. This ideal for meritocracy motivated the impulse for public education and popular elections from the founding fathers. Jefferson believed that elections would lead to the:

…separation of of the aristoi from the pseudo-aristoi, of the wheat from the chaff.

The Corruptibility of the Public

Adams, on the other hand, was not so optimistic about the potential for meritocracy. Rather than promoting the wisest and most virtuous, Adam believed that society would continue to extoll the well-spoken, well-born, and well-to-do. Adams believed the historical record of civilizations from ancient times through modernity displayed this persistent and pernicious stubbornness of a pseudo-aristocracy to remain in power, even in the supposedly free land of America:

Go into every village in New England and you will find that the office of justice of the peace, and even the place of representative, which has ever depended on the freest election of the people, have generally descended from generation to generation, in three or four families at most.

Jefferson presupposed that in a democratic society the most talented would rise to the top, but Adams flips the logic on its head. For Adams, a natural aristocrat is simply any individual who has the means to gain an outsized influence in society, and he argues that it is exactly the wealthy and well-born that are best in this position:

The five pillars of aristocracy are beauty, wealth, birth, genius, and virtue. Any one of the first three can, at any time, overbear any one or both of the two last.

It is this obstinacy of an aristocratic class to cling to power that drove Adams’ political theory. If free elections were not enough to prevent an aristocracy, there would be a need for institutional safeguards to protect the common people from such a class.

This is the justification for Adams’ proposals, proposals which he ironically is labeled as a monarchist for defending. A strong executive power elected by the common vote could keep an aristocratic Senate in line, a House of Lords could curtail the ambitions of the aristocracy by consigning their power to a specific house of Congress, titles of honor could channel the aristocrats’ lust for power towards the public good instead of amassing more power and wealth.

The challenges posed by aristocracy, whether natural or pseudo, whether benevolent or malevolent, whether meritocratic or hereditary, was the driving threat behind the theory of two of America’s most original political philosophers, Adams and Jefferson.

Meritocracy in China

Over two thousand years before the founding fathers, Chinese political theorists were already grappling with the issue of aristocracy and meritocracy. Confucian scholars built governments around the principle of “elevating the worthy and employing the able” (shang xian shi neng 尚賢使能).3 As the Chinese academic researcher Yuri Pines argues, Confucius himself was rather ambivalent about meritocracy.

Confucius' radical innovation was to imbue the term “noble man” (junzi 君子) with an ethical essence. If what makes a man noble is not his birth but his virtue, then even the common man (Shi 士) could attain the status of nobility through ethical behavior. Although the noble man is ethical, he still strives for public recognition:

“The noble man is pained if by the end of his life his name is not mentioned” (Lunyu 15.20); he speaks dismissively of those who failed to establish their renown by the age of forty or fifty (Lunyu 9.24), and appears to be greatly annoyed by a remark that despite his broad learning his own name is not widely known (Lunyu 9.2).

Confucius was not specific on how exactly these virtuous individuals would rise to power. This became a problem for his followers and led to various disagreements as Confucianism developed. Mozi, a former follower of Confucius, split off and started his own school of thought in contrast to his old teacher.

Mozi, writing in the Warring States period of Chinese history, was dissatisfied with the ruling class, whom Mozi called the “rich and noble without any reason” (無故富貴). Here already we see a parallel dichotomy between the Chinese thinkers and the Americans. On the one hand are the virtuous junzi and the natural aristocracy [Confucius and Jefferson], and on the other hand are the pseudo-aristocracy and the ‘rich and noble without any reason’ [Mozi and Adams].

In sharp contrast to Confucius, Mozi believed that what made people ‘worthy and able’ was not virtue but intellectual ability. This change in emphasis had the potential to solve a number of problems.

First, the issue of identifying virtue was much more difficult than identifying intellectual ability. Intellect, or some form of it, can be objectively assessed on an exam, whereas virtue is much more subjective. The reformer Shang complained:

Elevation of the worthy and the able is what the world calls “orderly rule”: that is why orderly rule is in turmoil. What the world calls a “worthy” is one who is defined as upright, but those who define him as good and upright are his clique.

In the Tang Dynasty, “the evaluation of ethics was based on a poem a candidate wrote within a specified timeframe”, which does not inspire confidence.4

Second, virtue can easily be faked by cunning and ambitious politicians. Ambitious people were motivated to take virtue to the absurd extreme:

…some men-of-service went as far as adopting eccentric modes of behavior, such as excessive purism, overt disdain to the office, provocative and confrontational stance toward the rulers, and the like. Much to the chagrin of thinkers of different ideological affiliations, these eccentrics could from time to time succeed in getting public acclaim and eventually coming into the ruler’s sight. And this could cause a useless eccentric to be offered a position of power and authority.

On the other hand, defining merit as intellectual ability has its own problems. First, the government would be run by soulless and possibly evil-spirited men. Second, intellectual ability is no guarantee of political skill. A pair of reformers known as 'the Two Chengs' remarked that the examination system led to rules that only “have encyclopedic knowledge” (博闻强记).5

According to Pei, the Wan Dynasty synthesized these two competing strains to create a political system that tempered the extremes of both while still meanwhile elevating the worthy, both as virtuous and intellectually capable.

Aristocracy Today

In a cover issue for The Atlantic magazine in 2018, the journalist Matthew Stewart wrote an essay called ‘The Birth of the New American Aristocracy’. Stewart condemns the decline of social mobility in American and places the blame on elite capture:

The meritocratic class has mastered the old trick of consolidating wealth and passing privilege along at the expense of other people’s children.

Gates to social mobility such as education, jobs, and other resources are either hoarded by the elite or manipulated to their advantage. The idea of an American aristocracy is not new, as we saw earlier from the debate between Jefferson and Adams. More recently, the specter of the ‘Boston Brahmin’ elite social class is a common trope to Americans.

Consider the current debate over standardized testing for college admissions in the US, which was actually inspired by the Chinese examination system. Some believe that efforts to remove standardized testing requirements from the college admissions process will make the system more meritocratic because wealthy students have easier access to resources and testing books, while others worry that removing testing requirements will only make the system even easier to game for an aristocracy. As discussed below, the Chinese have struggled with this problem throughout their history.

The idea of elite capture is not foreign to the Chinese either. In the Han Dynasty, the Recommendation System was introduced so that local citizens could recommend each other for public service.

After the middle of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE), however, the more powerful families controlled the main power of recommendation, and most of the recommended people came from noble families. The recommendation system lost its initial function of selecting and promoting competent and virtuous officials and degenerated into a way to protect the interests of certain families. Political hierarchies ossified, and rulers ruled for the interests of established elites.6

To fix this problem, the Liu Song Dynasty introduced a ranking system in which recruiters would travel and rank candidates on objective scales.

Unfortunately, the new selection system gradually became frozen…Powerful families gradually took charge of the positions of local recruiters, thus entirely controlling the ranking system.

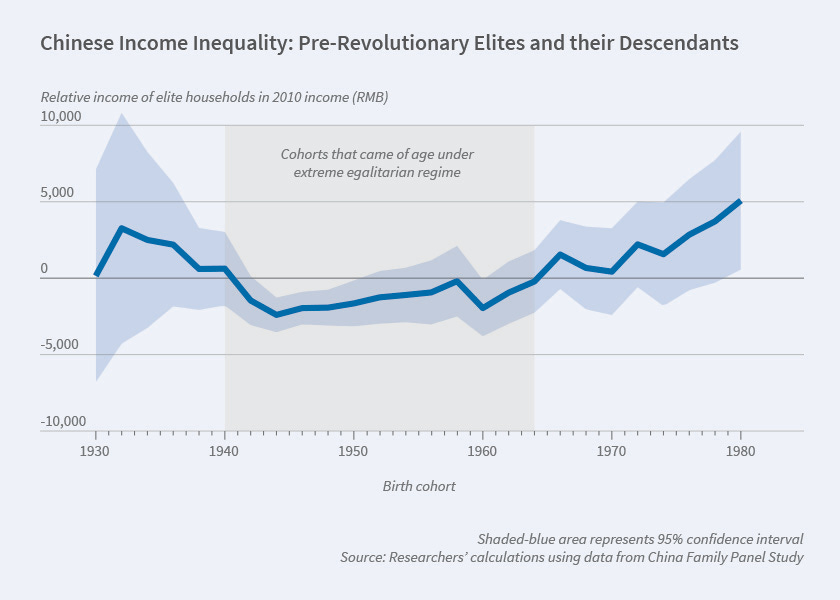

These examples of elite capture anticipate and justify Adams’ belief that aristocracies would always spring back from reforms to seize power. What is even more striking, researchers have found that generational wealth can survive even radical Communist revolutions.7 In China, the relative income of elite families exceeds what it was before the Revolution.

One of the most extreme attempts in history to eliminate advantages of the elite and eradicate economic and educational inequality succeeded only in the short term.

If both communist China and democratic-capitalist America cannot stave off the threat of aristocracy, it suggests that Adams and the early Confucians were wise to center their political philosophies around the problems of aristocracy and meritocracy.

Mayville, cited infra, notes a few exceptions of scholars that did not underrate Adams’ political thought: C. Wright Mills, Judith Shklar, and Hannah Arrendt. It is therefore unfair to say that Adams is universally maligned and ignored.

Letter from Adams to Jefferson, dated July 13th, 1813, available online here. The quote is taken from ‘John Adams and the Fear of American Oligarchy’ by Luke Mayville, endnote 7 of the introduction. All quotes from Adams and the general argument of this section are gleaned from Mayville’s book.

This section draws from Yuri Pines, ‘Pitfalls of Meritocracy: “Elevating the Worthy” in Early Chinese Thought’ and other papers cited.

Notes on Meritocracy: Insights from Tang’s Civil Servant Exam and Poetry, Bernard Yeung. Shockingly, Yeung cites a study in which empirical evidence was found for a “positive association between the artistic quality of poems and their author's’ ethics”. See footnote 2.

Wang Pei, ‘Debates on Political Meritocracy in China: A Historical Perspective’, 2017.

Daniel Bell & Wang Pei, ‘Just Hierarchy’, 2020.

Alesina et al., ‘Persistence Despite Revolutions’, 2021.

"merit", "worthiness" and "ability" in regards to what, exactly?

without a definition of the parameter under measure, all such talk is rationalization for why the status quo exists in the form it is currently.

also---there's nothing to stop fools from having good ideas. in fact, for all we know, most of our knowledge was derived that way regardless of the great names of history. since most of our knowledge is built up gradually by happenstance, accident or a fool with a good idea trying new things.