Reading Length: 15 Minutes

Keywords: Philosophy, Metaphysics, Plato, Kant

Visitor: Well then, do you say that knowing and being known are cases of doing, or having something done, or both? Is one of them doing and the other having something done? Or is neither a case of either?

Theaetetus: Obviously neither is a case of either, since otherwise they’d be saying something contrary to what they said before.

Visitor: Oh, I see. You mean that if knowing is doing something, then necessarily what is known has something done to it. When being is known by knowledge, according to this account, then insofar as its known its changed by having something done to it—which we say wouldn’t happen to something that’s at rest.

Theaetetus: That’s correct.

In Plato’s dialogue Sophist, a visitor from Elea argues with the young Theaetetus about the definition of being.1 To separate the important Platonic difference between being and coming-to-be, Theaetetus posits that “coming-to-be has the capacity to do something or have something done to it”.

This presents a problem, however, because if being can be known, then it could be argued that being is just like becoming-to-be in it’s capacity to do something or have something done to it. How so? As we see in the above quotation, if knowing something is the same as having something done to it, then the proof is complete.

Laid out formally, the argument is:

P1: coming-to-be has the capacity to do or have something done

P2: being can be known

P3: being is known

P4: something that can be known is changed

P5: to change is to have the capacity to have something done to it

A1: being has the capacity to have something done to it

C: being and coming-to-be are commensurable in this regard

Following this argument, we have failed to properly distinguish between being and coming-to-be. For the purposes of the present essay the context for which this argument serves in the broader dialogue will be ignored.2 What we will focus on is the perplexing claim stated in P4: something that can be known is changed.

Plato presents this premise as entirely self-evident and obvious. No further discussion is provided to support the claim, and the interlocuter Theaetetus accepts it without complaint. But on further examination the statement is puzzling. How could knowing something cause it to change?

If I see an object on the table, and come to recognize it as an apple, I have not caused any change in the object. The object was and still is an apple, despite my knowledge about it. My knowledge has certainly changed, but that is not the argument provided by Plato.

This peculiarity has been picked up by a number of Platonic scholars. G. E. L. Owen calls it “preposterous” and “a prima facie absurdity”.3 How does Owen attempt to solve this puzzle?

History as Change

Owen draws on a different dialogue of Plato’s, the Timaeus, where Plato argues that that which is changeless has no past or future:

That which is always unchangingly in the same state cannot be growing older or younger by the lapse of time. It cannot ever become so, it cannot have become so at present, it will not be so hereafter. And in general nothing can belong to it of all the things that the process of becoming attaches to the shifting things we perceive.

What Owen takes this now-classic statement to mean is that something that is unchangeable cannot have a history. Therefore, if something can be proven to have a history, it is changeable. How does this help us prove that to know is to change?

Let’s return to the example of the apple. In my coming to know the apple, the apple now has a history. It used to be not known by me, and now it is known as an apple. But if the apple has a history, and my knowing the apple gave the apple its history, then my knowing the apple has changed the apple.

Owen summarizes: “For on such an account it is sufficient condition of change that something should become true of the subject at some time that was not true before…”

Does this argument work? The logic follows, but Owen has solved one puzzling proposition by slipping in another.4 In his paper he marshals a considerable amount of evidence that Plato does indeed think that having a history makes something changeable, but it is not clear that this is any less puzzling than our original proposition.

Most pressing is the fact that if knowing something causes something to have a history, then every single conceivable object of human thought is changeable, otherwise it could not be known. The unchangeable, being, would be unknowable, which is an unacceptable conclusion. This is stated by Plato via the visitor:

And so, Theaetetus, it turns out that if no beings change then nothing anywhere possess any intelligence about anything.

Clearly being must be able to change, so this attempt at a solution is unworkable.

Cambridge Change

We return to the question of how it can be that to know something is to change it. One escape hatch used by scholars is to invoke the concept of ‘Cambridge change’. Popularized by Geach:

“ ‘The thing called “x” has changed if we have “F(x) at time t” true and “F(x) at time t1” false, for some interpretation of “F”, “t”, and “t1”.’

Cambridge change is thus an interpretative, relational change.5 Let’s return to the example of the apple. If, at time t, I thought the apple was a pear, but I now realize at time t1 that it is an apple, then F(x) at t1 is false, so we have the Cambridge relational change.

This seems like a promising avenue, and indeed it has been taken up by many scholars. To take one example, Reeve in his own survey of the puzzle concludes “It is enough if it changes ‘Cambridge’ fashion in relation to something else’.6

What is problematic about this move, and what Reeve makes explicit, is that the concept of change has now been split in twain. There is essential, fundamental change and there is interpretive, relational Cambridge change. We can now have our cake and eat it too. Being can be both changeless in one respect and changing in another.

This is unsatisfactory for a number of reasons. First there is little textual evidence that Plato ever considered the notion of Cambridge change. If the solution to the puzzle were to simply invent another parallel concept of change out of whole cloth, why would Plato not make this step explicit? The multiplication of concepts is just as liable to lead to obfuscation as it is to elucidation.

Second, this solution still leaves tricky metaphysical problems. As Irani points out, a key Platonic tenet is that the Forms are timeless. Cambridge change, however, necessarily relies on time as an index.7 If Forms can be Cambridge changed, then they must partake of time and lose their timelessness. We solve one puzzle by knocking another leg from the stool.8

Any solution to this puzzle seems to leave us worse off than we started. But what if Plato was just anticipating two millennia of scientific progress?

Quantum Physics and the Observer Effect

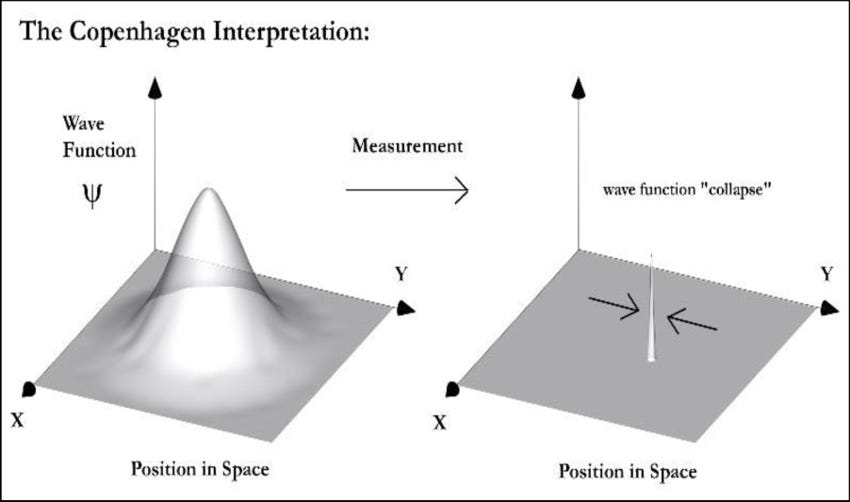

In quantum physics, the observer effect is a related to the the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. The physicist Heisenberg discovered in 1927 that it is impossible to determine both the position and momentum of subatomic particles Importantly, this holds true no matter how precise the method of observation is. Even with a theoretically perfect microscope, there would still be uncertainty.

The link between Heisenberg Uncertainty and the Observer Effect hinges on the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics and the idea of a ‘wave collapse’ upon measurement, where the quantum possibilities disappear and coalesce into what has actually occurred.

If the observation precipitates the wave collapse, then we have a clear case of knowing something causing change in the object, in the essential sense that it has set the context in which the objective phenomena of the object can be measured.9

Even without Copenhagen quantum physics we can see how the observer effect pervades our sense of the world. Consider the difficulty of measuring the temperature of an object without simultaneously changing the temperature of that object because of how it was measured. The only way to know the temperature is by changing the temperature of the object.

Does this solve our Platonic puzzle? It is farcical to suggest that Plato had some premonition of quantum physics over two millennia ago, so this should be chalked up to an interesting coincidence rather than a buttress to his argument.10

The Kantian Escape Hatch

What if this entire project is misguided? What if it doesn’t even make sense to ask how an object could come to change by being known? In other words, is the question ‘is being changeable’ even coherent?

Immanuel Kant revolutionized metaphysics exactly by raising these questions and creating a distinction between analytic and synthetic concepts. To put it crudely, analytic concepts are mere playthings of the mind that have no connection to actual reality, they are merely logical. Synthetic concepts are employed on objects of the sensible intuition, that is, things that actually exist in the objective world, so they are properly metaphysical rather than merely logical.

If a concept can be shown to be analytic rather than synthetic, then it can be dismissed as non-metaphysical and ejected from debates over the possibility and extension of our knowledge about the world.

How can this distinction be drawn? For Kant, space and time are the grounding properties of the manifold of sensible objects. If a concept is presupposed to be timeless and/or spaceless, it can have no possible relation to sensible reality and is purely analytic.

If one tries to use rational thought to reason about analytic concepts, endless contradictions will appear. Kant illustrates these in a famous section of his Critique of Pure Reason on these so-called ‘antinomies’. For example, it can be argued persuasively that the world began at some point in time and also that the world is eternal. Both arguments are also defective, so the thinker is left in an endless contradiction.

The real problem, as Kant poses it, is that in this case the world is not a proper concept because it cannot cohere to the thinker in sensible intuition as an object proper, it is just an abstract idea that is hard to pin down what it could even mean. Therefore it is not surprising that the mind is unable to come to reasonable conclusions about the world.

Analytic concepts that have been developed a priori are only useful when applied to objects of experience. If they are applied to ‘a priori demonstrations’ of a purely logical nature, they will founder:

The failure in the use of such [analytic] principles which gives rise to skepticism, is found solely in cases where only a prior demonstrations can be required, because experience can neither affirm nor deny anything in regard to them. This failure consists in the fact that a prior demonstrations of equal strength, which establish precisely the opposite principles, are contained in the universal human reason.11

We see Kant employ this same move in his essay On a Discovery while discussing the (previously) metaphysical argument that the essences of things are unalterable:

To the proposition which belong merely to logic, but which through the ambiguity of their expression find their way into metaphysics, and thus, although really analytic, are regarded as synthetic, belongs also the proposition the essences of things are unalterable, i.e. one cannot modify anything in that which pertains essentially to their concept without a the same time giving up the concept itself.

Only this metaphysical motto is a poor identical proposition which has nothing at all to do with the existence of things and their possible or impossible alterations. Rather it belongs entirely to logic, and inculcates something which no one could dream of denying anyway…

To discuss questions like these are not even in the realm of metaphysics because they bear no relation to the physical world.

If one plays with mere concepts without considering their objective reality, then one can very easily bring forth thousands of illusory extensions of knowledge without needing intuition. Things are quite otherwise, however, when one endeavors to extend one’s knowledge of an object.

What status does that leave analytic concepts like being and other Platonic forms that cannot be given as an empirical object?

“…we must acknowledge that our concepts have no claim to be ranked as cognitions of objects, but only as Ideas, merely regulative principles in respect to objects which are given in intuition, but which can never be completely known in terms of their condition.

Again Kant emphasizes that analytic concepts have use only when they are employed to empirical ends. Being is not “given in intuition”, so concepts such as being do not even qualify as “merely regulative principles”, they are “empty”, entirely useless.

It is plain to see that this is a Kantian rejection of the Platonic realm of transcendence. If being and other Forms transcend reality, they will have no foundation in the physical world and be empty concepts, mere play-things of the mind. This is unacceptable to Plato, who considers the realm of Forms to be the realm of reality par excellence.

If these Platonic arguments so often end in contradictions and paradoxes, perhaps Kant was on to something with his revolutionary critique of metaphysics. The transcendental realm is slammed shut, and Kant is left back in the Socratic square one, left in a state of wondering:

For a truly genuine ascent, namely, to an other species of being than can in general be given to the senses, even the most perfect, another mode of intuition, which we have named intellectual…would be demanded. With such an understanding, not only would the categories no longer be required, but they would have absolutely no use.

But who can provide us with such an intuitive understanding, or if it lies concealed within us, who can acquaint us with it?

Plato, Sophist, translated by Nicholas P. White, Hackett, 1993. All quotations from the text refer to this translation. Emphasis in bold added.

Namely, Plato argues that being partakes of the forms of both changing and the unchanging, providing support for his broader theory that the forms can be blended together.

G. E. L. Owen, Plato and Parmenides on the Timeless Present, The Monist, 1966. All following quotations of Owen refer to this paper.

Vlastos, in An Ambiguity in the Sophist, 19870, finds the premise so implausible that he argues that Plato does not take it seriously. It is only ascribed to the ‘friends of the form’ and its rhetorical purpose is to show that their beliefs lead to contradictory outcomes. For Vlastos, Plato cannot concede the ‘metaphysical foundation of his whole system: the absolute unalterability of the Ideas’. But if the device used is the Socratic elenchus, the conclusion must be faulty, viz. that Being partakes of both change and stability. It is not clear that this statement is untenable with the broader system devised by Plato in the Sophist.

David Keyt follows Owen in his paper Plato’s Paradox That the Immutable is Unknowable, 1969. He closes by stating: “For a Platonist, after all, the history of concepts is the history of certain accidental attributes of Forms.’ Keyts combines Owen’s historical line of argument with the Aristotelian distinction between accidental and essential attributes.

P. T. Geach, God and the Soul, 1969. Quotation taken from Tushar Irani , Perfect Change in Plato’s Sophist 2022.

C. D. C. Reeve, Motion, Rest, and Dialectic in the Sophist, 1985.

See footnote 4.

Julius Moravcsik, in his influential paper Being and Meaning in the Sophist, is just one example of a scholar who takes the Cambridge change tact. He goes so far as to state “Needless to say, at no point is it asserted that the Forms undergo a change of their own nature if and when they are known. The forms are subject to change and motion only in the sense that dated (temporal) propositions are true of them.” Far from being needless, it is unclear how Moravcsik draws the connection between Cambridge change and motion. He simply asserts it as a proposition accepted by the interlocuters. But such propositions put us into this morass in the first place.

I am grateful to Conner and Amber Mallet for helping me secure a copy of this essay from the Penn State library.

Importantly, it is not the action of knowing that the experiment was done that causes change, but the action of doing the experiment itself. One could perform the experiment and close their eyes to the results, so that there is no causal connection between knowing and changing, but the only way to know is by eventually opening your eyes, so that knowing is still causally connected to the change. In other words, one can change without knowing, but one cannot know without changing.

Democritus did anticipate the atom, but reasoned through it on first principles. Plato makes no attempt at an observer-disturbance theory, so any link is unsupported unlike in the former case.

Immanuel Kant, On A Discovery…translated by Henry Allison in The Kant Eberhard Controversy, 1973. All following quotations from Kant are taken from this essay.